Sometimes I imagine

that the river Helen and I sit beside can be opened like a book, where I absorb the teachings, drink it up… instantly merged with the qualities of its essence.

What strikes me often about the Setétkwe Fraser is the smooth surface that moves so rapidly, a contrast to the churning movement of the water flowing through the valleys and canyons. I reflect how history is like a river, flowing without us noticing, but ever connected to the past and future, with all the pieces churning and tumbling about with the impacts of our decisions.

When I do return to my books, articles and research regarding Indigenous Relations, the energy of the River comes with me. The imprints left in the spaces around Xats’ull, for example, provide a framework that holds place-based practices that inform politics, environmentalism and our need to mend the fabric of our society’s web.

Conversations with my second mentor, Meeka Morgan, taught me to observe and listen much the same way Helen taught me to sit with the River. The amazing thing is, it mattered not if we were discussing festival organization as fellow arts organizers, or her personal values regarding socio-political activities in our communities, if I really listened, I gained access to a worldview that anchored into her Indigenous “grounded normativity” – this is a term Leanne Betasamosake Simpson uses to express the ‘beingness’ of pre-contact Indigenous nations, who developed a set of actions, protocols, relationships and kinships with the whole of the creation to continue creation. (From As We Have Always Done: Indigenous Freedom Through Radical Resistance, p. 24). If we aim to understand the ‘other’s’ perspective, then anchoring ourselves in active listening that allows us to truly hear is essential.

And then, we must seek out the lesser-known stories that flow across history.

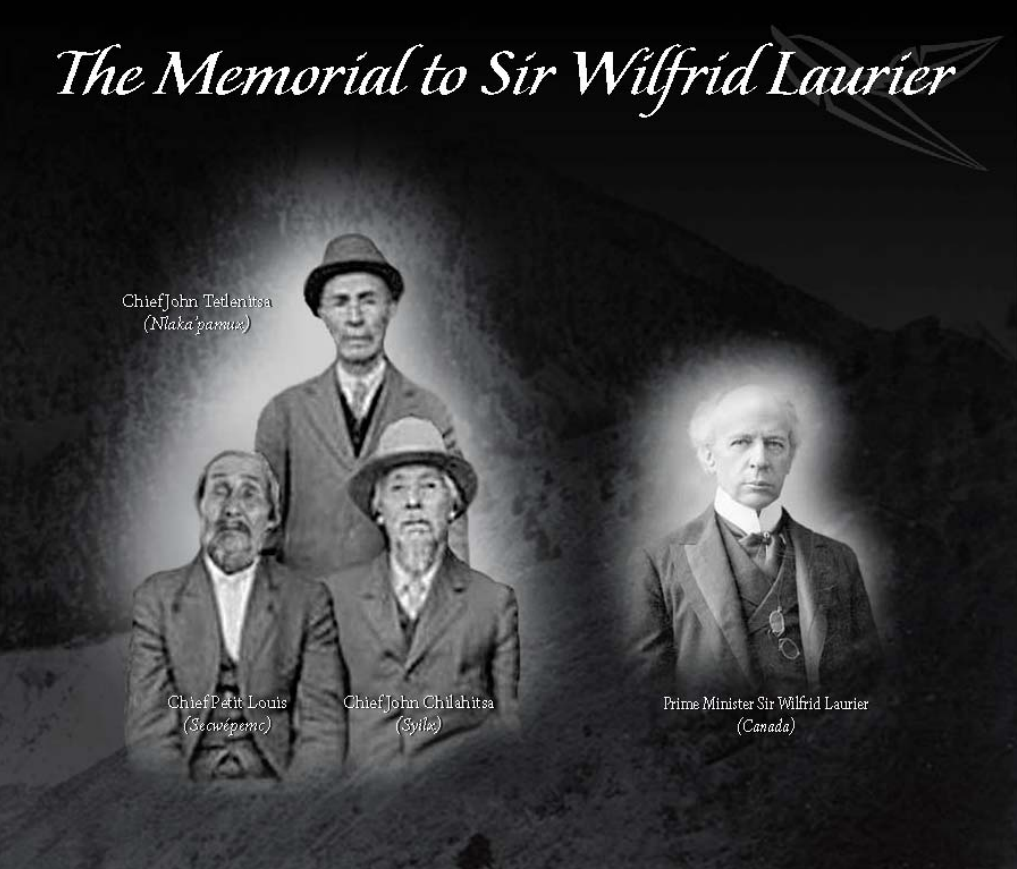

From the front page of The Memorial to Wilfred Laurier, a document presented to the head of State on August 25th, 1910, In Kamloops. Multiple Chiefs of the Interior First Nations drafted the letter.

Through Meeka, I was introduced to “The Memorial to Sir Wilfred Laurier from the Chiefs of the Shushwap (Secwepemc), Okanagan (Syilx) and Couteau (Nlakaʼpamux) Tribes of British Columbia” from 1910. As tensions from unmanaged settlement and increasing dispossession of lands by the Interior Nations grew heavy, a compelling document was drafted to document the situation and seek resolution from the Canadian head of state. In clear, respectful, and concise language, these Chiefs explained the systemic denial of their rights. A picture of organized dispossession and even oppression emerges, and hindsight shows us how little was done to settle the ‘Land Question’ in British Columbia. With our present lens, it is all too clear that harm was done.

From the Memorial to Laurier from 1910, I am swept up by the current of hope and goodwill that wends through the document:

“Some of our Chiefs said, “These people wish to be partners with us in our country. We must, therefore, be the same as brothers to them and live as one family. We will share equally in everything-half and half-in land, water and timber, and so on. What is ours will be theirs and what is theirs will be ours. We will help each other to be great and good.”

I believe it is right to ask of ourselves today, why didn’t the governors of the past take the route of shared values, caring communities and sustainable approaches to resources?

With dedicated learning / un-learning, and by hearing from the diaspora of Indigenous voices, layers upon layers of untruths are stripped away. The hidden intent of colonial powers (including current governments) to diminish or eliminate Indigenous rights so that ‘governments’ could gain resources surfaces over and again. Prioritizing ‘Truth’ as it applies to settler colonialism encompasses everything from resource extraction goals to cultural genocide, to current issues that involve incarceration rates, the Missing and Murdered, access to clean water, children and youth in care, and so much more. It reveals belittling stereotypes employed by the dominant culture honed to devalue the lives of Indigenous people and communities, who were frequently isolated and removed to sub-par land bases called reserves. (For a devastating account of the local distress Chief Williams was facing in 1879, see the reference below.)

The isolation and removal of Indigenous people worked in multiple ways, first as an attempt to contain the people that posed a threat to extractive goals by industry, but also giving less chance that settlers discover the lies employed against Indigenous people and communities. It’s a vicious cycle, compounded by intergenerational traumas, and the wounds of residential schools that touch most Indigenous families.

Here, in the ‘Memorial to Sir Wilfred Laurier’, we have documented proof that Indigenous leadership took great care and concern to communicate, to advocate for their Nations, to elucidate the rest of the world about their concepts of ‘International’ relations from their grounded normativity and place-based politics. In the discomfort of reading this testament from these Chiefs, itself an act of early allyship by its translator, anthropologist James Teit, emotions like shame and anger DO arise, because the level of authenticity and respect contained in the words from the Chiefs were unmet from any level of government or industry for over a century.

Let water wash the old away… if we settlers cling to the past, or refuse to open to change, our systems become brittle. Water transforms, then can heal and nourish if we allow it, just as the truth does. Let’s allow the water of truth to seep up into the roots of our current ways, let us be informed by the Truth and grow into new and flexible shapes as a society.

Letter by Chief William, 1879, to the British Times Colonist

T’exelc / Williams Lake First Nation’s Chief William, 1867.

The Letter that follows anchors us in a story that was ignored by governing structures and settlers.

Photo: Archives Canada (F. Dally)

Letter from the second Chief William, 1879. “I am an Indian Chief and my people are threatened by starvation. The white men have taken all the land and all the fish. A vast country was ours. It is all gone. The noise of the threshing machine and the wagon has frightened the deer and the beaver. We have nothing to eat. We cannot live on the air, and we must die. My people are sick. My young men are angry. All the Indians from Canoe Creek to the headwaters of the Fraser say ‘William is an old woman, he sleeps and starves in silence.’

I am old and feeble and my authority diminishes every day. I am sorely puzzled. I do not know what to say next week when the chiefs are assembled in council. A war with the white man will end in our destruction, but death in war is not so bad as death by starvation. The land on which my people lived for five hundred years was taken by a white man; he has piles of wheat and herds of cattle. We have nothing – not an acre. Another white man has enclosed the graves in which the ashes of our fathers rest, and we may live to see their bones turned over by his plough! Any white man can take three hundred and twenty acres of our land and the Indian dare not touch an acre. Her Majesty sent me a coat, two ploughs and some turnip seed. The coat will not keep away the hunger; the ploughs are idle and the seed is useless because we have no land.

All our people are willing to work because they know they must work like the white man or die. They work for the white man. Mr. Bates was a good friend. He would not have a white man if he could get an Indian. My young men can plough and mow and cut corn with a cradle. Now, what I want to say is this – THERE WILL BE TROUBLE, SURE. The whites have taken all the salmon and all the land and my people will not starve in peace. Good friends to the Indian say that ‘her Majesty loves her Indian subjects and will do justice.’ Justice is no use for a dead Indian.

They say ‘Mr. Sproat is coming to give you land.’ We hear he is a very good man, but he has no horse. He was at Hope last June and he has not yet arrived here. Her Majesty ought to give him a horse and let justice come fast to the starving Indians. Land, land, a little of our own land, that is all we ask from her Majesty. If we had the deer and the salmon we could live by hunting and fishing.

We have nothing now and here comes the cold and the snow. Maybe the white man thinks we can live on snow. We can make fires to make people warm – that is what we can do. Wood will burn. We are not stones. WILLIAM, Chief of the Williams Lake Indians (Williams Lake Indian Band)

Learning Resources:

— Leanne Betasamosake Simpson (leannesimpson.ca)

memorial-to-sir-wilfred-laurier_Page_1.pdf (sfu.ca)

History at the Confluence: This most important document in Kamloops’ history (thewrennews.ca)